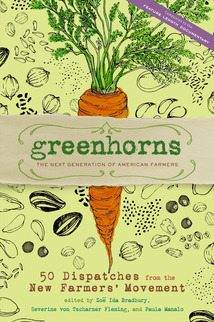

From the upcoming book, Greenhorns: 50 Dispatches from the New Farmers’ Movement:

From the upcoming book, Greenhorns: 50 Dispatches from the New Farmers’ Movement:

The Value of Our Produce

By Ben JamesLast week at market a customer complained about the price of our dill (two dollars for a not-huge bunch). He said the price was an outrage, but he was smiling, so I was too confused to ask why he was going ahead and buying the dill, or even how he’d arrived at his notion of its value.

This is not an unusual occurrence; every week at market we get at least one or two potential customers who shake their heads in dismay at a $2.75 head of lettuce or a $4.00 pint of strawberries. Sometimes I engage in conversation, sometimes I don’t. I try not to get defensive, and I frequently encourage a customer not to buy the product, offering suggestions of where to find cheaper food, either at the market or elsewhere. I do my best not to reveal that the value of our produce is a question that regularly fills me with a tremendous amount of anxiety.

What is a carrot worth? A bunch of kale? A handful of berries? Too often, I find myself on the tractor making quick calculations in my head. For a bed of carrots, there are the soil amendments, the cover crop last fall, the chicken manure, the organic fertilizer, the plowing, tilling, seeding, irrigating, thinning, weeding, harvesting, washing, bunching, packing, and selling. Plus the cost of the tractors, implements, and fuel. Plus the cost of childcare and preschool. Plus, somehow, all the time spent on the computer (where does that fit in)? And I haven’t even mentioned the cost of the land (hundreds of thousands of dollars, in our case). The sheer number of labor hours and material and property costs that went into helping this soil produce these carrots. I ought to shellac the carrots and hang them on the wall.

For us, the value of our produce can be measured — at least imprecisely — by how hard we and our crew work to grow it.

But what if the workers were just slow weeding the carrots that day? Or what if the farmer himself is a hack? What if it takes him three seedings over that many weeks before he even manages to get a row of carrots to germinate? (I’m not naming names….) Should the customer be expected to pay for the incompetence of the grower?

Fortunately for me, I suppose, incompetence is much less an issue than the very nature of the project we’ve undertaken. We grow many different crops (46 and counting) on a small amount of land (11 acres), and this — as each of our variously weedy rows can attest — is a fundamentally inefficient thing to do. Although we strategize endlessly about how to make our operation run more smoothly — setting up systems, buying new equipment, instructing and correcting the crew — it’s a hopeless endeavor. Eventually, we’ll need either to substantially increase the size of our farm or shift our marketing strategy to grow only a handful of the most profitable crops. Until then, we mechanize whenever and wherever we can, but even the potato harvester and the water-wheel transplanter I’ve got my eye on would have a hard time paying for themselves at our scale, and so we’re left with that most versatile and least cost-effective of technologies: our hands.

All of our hands: Oona’s and mine, the hands of our four full-time employees, plus the scattered extra people who frequently fill in the week. And if there’s anything to match the anxiety of assigning a value to our produce, it is, for me, the challenge of figuring out how much to pay our crew (currently at least $9 an hour).

I was raised by leftist labor organizers in Kentucky, Detroit, and Queens, and it’s fair to say that the plight of the Big Boss Man was not a frequent topic of conversation around our breakfast table. I learned the importance of work and the compromised position of the worker, and I was taught to question at every level the judgment and the ethics of the person in charge. So, to that small subset of the American population that was raised in the inner-city by Marxists before going on to start small, diversified farms and employ several recent college graduates, I say, “Hey, I can relate.” It’s not easy to be a boss, especially when your workers are getting paid more than you are, the pigweed is as high as your navel, and the man at the farmers’ market is smiling while he complains about the price of your dill.

And although some parts of Oona’s and my situation are unusual, the basic equation is not: Small-scale farmers and their employees are earning nowhere near the money they should be making for the endless, all-encompassing, dangerous, exhausting work they’re doing. Easy to say, but difficult to figure out what to do about it, whether you’re the farmer or the customer. Read more…